---by Michael Zwerin---

the village VOICE, March 9th 1967

I went. Public relations, however, ended with the release because the concert looked like a total economic disaster. The theatre was maybe 10 percent filled and a good deal of those seemed to be the Ayler family. The 25th was a very cold night and the prices were an absolutely frigid $3, $4, and $5. There had been little advertising other than the posters in front of the theatre, which has a capacity of about 2500. Whoever booked it was an optimist with a poor memory because only two months ago, when Ayler played the Village Vanguard, even that little room was far from packed. Audiences seem to stay away from Albert Ayler—a shy, sad-looking little man who has something to say.

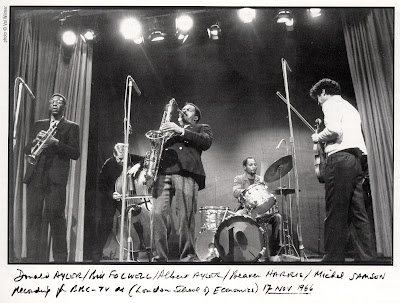

The Albert Ayler Octet—Albert Ayler, alto and tenor saxophone; Donald Ayler, trumpet; Michel Sampson, violin; Beaver Harris, drums; Bill Folwell and Alan Silva, basses; Joel Friedman, cello; and Call Cobbs, harpsichord. Beforehand, in the lobby, Cobbs said he wasn’t playing because he had just found out there was no harpsichord in the place. “The music wouldn’t sound right on a piano,” he explained. So strike him, and add George Steele on trombone.

Also add Mary Parks on MC—an avant-garde chick. “Good—evening—space friends,” she said, her golden gown sparkling reflections no doubt from Venus, “tonight—we—will—hear a—concent—of—music—of the—year two—thousand.” With free punctuation she got the concert started 45 minutes late, not apologizing for the delay either. I thought of John Cage’s line about “the importance of being on time for anyone involved with the art of music.” But there’s a logical unreality to Albert’s music—kind of like a Ray Bradbury story—which seems to penetrate people even before he starts playing and the waiting was perfectly okay with everybody.

The tunes, all written by Albert, have names like “Light in Darkness,” “Heavenly Home,” “Spirits Rebel,” and “Truth is Marching In.” They are fiercely tonal, resembling primitive marches or folk songs, and use only three chords, if that many. Improvisation is abstract, spaced by recapitulation of the theme, usually played Germanically by Don Ayler’s trumpet along with a Liszt – cadenza – gone-wild on Sampson’s fiddle. Albert solos most of the time—on some tunes the others do not play at all other than behind him or on the ensembles.

Scot LaFaro revolutionized the jazz bass before he was killed in an automobile accident in the late ‘50s. Instead of just walking , he played swift, complex, melodic obligatos and since then many bass players have delusions of violins. They began using the bow more often and, whether arco or pizzicato, forever lean way over the instrument, both hands near the bridge, eeking the most unlikely harmonies from their instrument. Truly astounding. The only trouble is that, with the increased importance of percussion in the new jazz, the audience usually can’t hear their cascades of notes. At the Village Theatre, though, the trouble was stupid balance, unfortunately common with the avant-garde, because Beaver Harris is one of the better free drummers, keeping a pulse, no matter how abstractly, and keeping it with sensible dynamics.

Anyway, Folwell and Silva made a hell of a visual impression, scooting all over their instruments. I’m pretty sure they were playing some impressive stuff. As a matter of fact, a couple of duets between them, with everybody else tacited, were very lovely and exciting. And one tune featured Albert plus only the cello and two basses. It was cloud-like and dewy music. Albert, who did not squeak on this one, was brilliant in his abstractions, instinct supplying all of the criteria needed. And the three strings were empathetic to perfection.

Now, about Albert’s squeaks…Squeaking is nothing new of course. Illinois Jacquet and Flip Phillips did that years ago. It’s a way of transmitting energy—but it’s too easy a way and I mistrust it. Besides, it hurts my ears. Albert’s squeaking is the low point of his playing. He starts doing it without continuity and stops abruptly without form—an insert, out of context. Few tenor players can get around up there as he can, but if he wants to hear those sounds, why not take up the piccolo or something.

Donald Ayler’s trumpet playing impresses me as being pure chance—no choice—a random combination of fast-flipping valves and embouchure adjustments. Every solo sounds alike. He rarely holds a sustained note. When he does, however, a pleasant sound comes out (I mean that as a compliment). More of that would be nice.

Albert’s music is strangely warm and loving. The freneticism I once minded so much seems less pronounced now than two years ago. Maybe I am better tuned to him—or possibly he has matured some. Either way, I was wrapped up in the music and stayed until the end of his concert, something I’ve never wanted to do before.

But without more artistic handling, Ayler will continue to be only the obscure underground hero he now is. That’s a shame too, because, given the chance to hear it, a lot of people could find his music important."